Welcome to our series of 100 interviews we will be holding with photographers who use mirrorless cameras for their work! “Switching to a smaller and lighter system” has become somewhat of a buzz phrase as of late, but many working photographers take this philosophy seriously. From medical reasons such as resolving back and shoulder pain to the simple realisation that bigger does not mean better, photographers are turning to mirrorless systems now more than ever before.

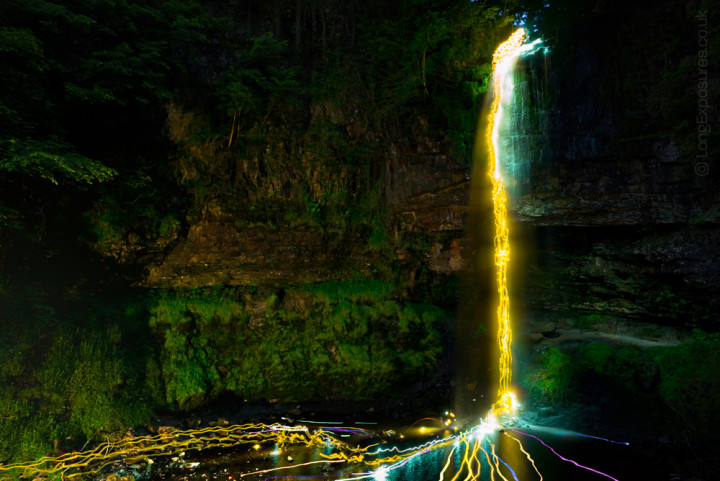

This week’s interview is with Andrew Whyte, a long exposure photographer who creates original images using cutting-edge equipment and innovative techniques. His weapon of choice is none other than the low-light demon, the Sony A7s.

Visit Andrew’s photography website and check out his work on Facebook and Twitter.

All images in this article are property of Andrew Whyte and are published with permission.

1. Who is ‘Andrew Whyte’ in three simple sentences?

I’m a commercial photographer based on the south coast of England. In long exposure night photography I’ve developed a narrow field of specialism within which I practice the art and try to demystify the science- through presentations, workshops and written features. The quality I value most in any photograph- whether mine, a family snap or an iconic portrait- is integrity to the original scene.

2. Why did you decide to specialise in long exposures and what drew you to the genre in the first place?

Ending up as a dedicated night photographer was unplanned. Photography has been a significant passion of mine since I was very young. For my sixth or seventh birthday I got my first camera and I’ve never been without one since. My work experience from school was with a professional photographer, and left a strong positive impression, some of which I still benefit from now, two decades later (thanks Michel!). But it took the birth of my second child (in 2007) to inspire a change in career to photography. Thing was, I’d underestimated several things. Parenting, for a start- I had little time to pursue photography during the day. And, at the time, my dislike of post-processing was strong yet I was constantly frustrated by my daylight images.

Almost on a whim, one evening I set the camera up in the back of my car to capture my journey home through the city. The resultant image wasn’t perfect- nor was it that commercial- but I knew I’d found a starting point that fed my fascination with portraying movement in still images. Here was something that worked straight from the camera. Literally from that moment on I invested all my photographic efforts in pursuing long exposures & light trails. Shortly after, I shot my first star trails and night sky images, setting myself up for a future of sleepless summers, chasing the Milky Way at dark sky landscapes around the country.

3. What are the biggest challenges associated with long exposure photography (astrophotography and light painting)?

On a human level, the biggest challenge with any night shoot is stamina. It’s physically & mentally draining to maintain focus well into the night, particularly if shooting solo. Coffee & sugary snacks help, most definitely, as do my Brasher boot & sock combo, decent outdoor clothes & a good hat. The moment you feel the cold you might as well pack up and go home, it becomes all consuming.

In terms of technique, the challenges are many but with experience they become a series of hills rather than mountains: composition (use a torch to locate the corners of your frame through the viewfinder); focus (again, use of a torch is essential); metering (shoot a test shot at high-ISO & wide aperture to gain an understanding of light levels; calculate from there). Don’t get me started on the weather, though. I think it’s much harder at night than in daytime to create something in bad conditions. Astro shoots depend on near-cloudless skies and, even if you keep an open mind, the kind of location that works for astro may not support a lightpainting session.

Balancing ambient light with any light you want to add in is a further complication. Not just the light levels themselves- think about how much brighter your own light would need to be to make an impression in a streetlit area vs a remote site. White balance from mixed light sources is also a big challenge, particularly how that has an impact on colour saturation across the spectrum.

4. Why did you choose the Sony A7s as your main camera?

I was in the market for a new camera last year when a call came in from Sony’s PR team. They needed an experienced photographer to shoot some astro images to showcase the low-light strengths of the A7s.

For the assignment it was important that the images were created independently, rather than coming from, say, a Sony Ambassador.

As a Nikon user I offered that unbiased position. But as soon as I saw the first RAW file from Northumberland’s dark skies I knew the Nikon’s days were numbered and an A7s was what I needed in my kit bag. Since then I’ve sold my Nikon bodies, added a second A7s and the Sony Zeiss 16-35 FE. I usually use my second body with one of my Nikon primes, mounted via a cheap adapter. I remain independent, although Sony have generously looked after me with loaned lenses on a couple of occasions.

5. What has been your most difficult shoot so far with the Sony A7s? How did you overcome the difficulties?

Every shoot has its own challenges, it’s just something you learn to live with. I think I experienced the biggest array of difficulties on that first shoot. It was late twilight when I arrived at Sycamore Gap on Hadrian’s Wall, 500 miles from home. 6pm or thereabouts on an October evening. Before I’d even taken a shot, I’d sunk ankle deep into some of Northumberland’s boggiest farmland. My boots were just about holding the dampness at bay.

Setting the camera up for my first image, the magnitude of the task ahead sunk in. With 10 landscape astro images to complete before dawn, now was not the time to find fault with the camera. It was a baptism of fire to get to grips with an entirely new system & interface in such conditions. All the controls were in different places (to the Nikon), I hadn’t used an EVF since a primitive Fuji in about 2003, the f/4 lenses meant pushing the ISO at least a stop further than I’d usually shoot. Fortunately, from the very first shot, the A7s delivered. I had a wobble later when it clouded over and started raining with just two shots in the bag, but the sky then cleared for the rest of the night and my confidence in the camera continued to grow.

The biggest thing to catch me out, I think, was the image stabilisation. It took several shots in the same location to understand why my startrails were all over the place, even in 30-second exposures. When any IS camera/ lens is tripod mounted, it seems the stabilisation tries to compensate for vibration that’s not there. Result: unsharp images. Switching off Steadyshot made the difference.

It was also the first shoot I used an EVF to focus manually w/ focus magnification & peaking. It’s asking a lot of an f/4 lens to do that in a true dark sky location, but the Sony Zeiss 55mm f/1.8 was insanely good in those conditions. I’m a true EVF convert now.

6. What kind of tools and lighting equipment do you use to create the various effects in your long exposures?

A couple of decent torches are a must as they’re so versatile, for workspace illumination and lighting the scene, wholly or in parts. I think the only dedicated light tool I have is what I use to create the colour changing “ribbon”. Most other light sources begin as £5 sets of fairy lights before being hacked about to change colour or shape. The dome light paintings are made by a string of lights around a bike wheel. Others get attached to lightstands or items of clothing before some experimental shots lead to refinements then, ultimately, dismantling and reuse.

7. If you had to recommend three must-have accessories for your A7s, what would they be?

Installable apps. I’d definitely recommend the “Touchless Shutter” & “Smart Remote” apps, with which you can almost survive without the RM-VPR1 remote. Smart Remote in particular is handy on location as it gives me a view from within the composition- that’s almost as valuable as having an assistant, when added light is going to be involved.

Lens mount adapter. Without exception the Sony Zeiss lenses have been the best I’ve used- that’s 16-35, 24-70 & 70-200. Low distortion and sharp right into the corners, with minimal vignetting. But with their f/4 max apertures, those lenses ask a lot of the EVF in the darkest locations. A fast prime brings the EVF to life and I love that I can use my existing Nikon lenses on the A7s, it’s saved me a lot of money even if their quality is not quite up to the standard of the Sony Zeiss & Zeiss offerings.

Spare battery. The A7s battery life continues to impress. I’ve seen comments slating it but, for me, it’s a huge improvement over any camera I’ve used before. Typically I now get two hours or more exposure duration from a single NP-FW50. My longest single exposure has been 1h 40m & several times I’ve shot continuous sequences (for star trails etc) that have exceeded 1h 30m. Long exposure photography is demanding on battery life, though, so having spare(s) gives me confidence to be able to shoot as long as I need.

8. How do you prepare your composition? Do you storyboard it, plan everything before the shot, or create it on the shoot?

I like to do as much preparation as possible beforehand but you always pick up fresh information once you’re on site. Sometimes it’s hard to know the position of elements in the night sky, other times I might be struggling to get to grips with the scale of a landscape. I seldom storyboard although I might use my phone to compile a shot list and browse some reference images.

Often what works at nighttime is quite different to what you’d look for in daylight. An astro shoot, for instance, is going to want swathes of seemingly empty sky, to fill with starlight. You’ll still want an earthly element to anchor the scene, though, to give the sky some context. You’d seldom take a shot like that on a clear blue-sky day.

Similarly with lightpainting, I’ll usually have an idea of what I want to shoot but that can easily change on location, when the logistics of creating the shot start to materialise. It’s important to remain flexible but, generally speaking, the more I pre-visualise my outputs, the more successful the shoot goes.

9. What do you look for in a location when you plan a light painting shoot?

I’m very much a location photographer so, when it’s my choice, I’ll start by considering the story I’m trying to tell. That might be the light interacting with the location, or even just a shot that makes people stop and question what it is they’re looking at.

I’ll want somewhere with known ambient light conditions. It almost doesn’t matter what the conditions are, as long as they’re known, or controllable. I always shoot in full manual mode so the camera won’t ever compensate on my behalf if the conditions change part way through a shoot. I’m not a fan of streetlights, but having now embraced PP in a way I originally failed to, I’m happy to shoot lighting compositesstreet lit areas are no longer the no-go zones they once were. This is particularly applicable to my automotive images. The speed priority mode of the A7s offers both practical & hidden benefits here. Firstly, it’s immensely fast to end one frame and begin the next, so you miss nothing in the way of added lighting. Secondly, the preview screen stays on throughout, showing you the last shot to be completed. Very handy if you want to know if that frame was affected by external factors, such as oncoming headlights.

10. Do you generally work alone or do you have an assistant for more complicated shoots?

I imagine that being an assistant on a night shoot would be so dull- there’s so much dead time- so I usually work alone.

When I’m preparing for a commercial shoot I work on the assumption that each image is going to take at least an hour to perfect. Sometimes you strike lucky and nail the shot first time, but that’s seldom a case of setting up the tripod and pressing the button, then home. Usually a first-take success is the result of hours of forethought & vision, and years of experience.

Other times are even more demanding. I was recently briefed to create three shots between 9pm & midnight. The client joined me on location and for various reasons we couldn’t start ’til 10.30 and only wrapped at 4.20 am, 50 frames later. I don’t think they were expecting that! The struggles were nothing to do with the camera, though. More that the unique challenges of night photography are widely underestimated, sometimes even by me.

To come back to the original question, even on the occasions when there’s less dead time, I just feel like I don’t want to put others through the extended antisocial hours and subsequent malaise.

11. You say you also do a lot of commercial work. What kind of shots tend to be requested and how are your photographs generally used in publications?

Much of my commercial work is for PR assignments. It’s my favourite kind of job, as there’s usually a clear brief; a requirement that the images are only lightly edited (I still aspire to get as much as possible nailed in-camera); and a rapid turnaround to publication or usage.

I regularly shoot cars for private owners, and I also enjoy the evolutionary process of embarking on personal projects and seeing where they can take you. Some end with image licensing, others generate fresh commissions and more still go on the back burner, only for someone to call out of the blue 12 months after you started.

12. There are many great compact systems out there at the moment. If you hadn’t chosen to go down the Sony full-frame route, would you have chosen another mirrorless system? Which one and why?

Honestly, I don’t know. I might have stayed a Nikon user- there’s some great features on the “Retouch” menu of Nikon DSLRs that have helped me over the years. Low light performance of the latest Nikons is undoubtedly up there, but ISO for ISO at a much greater financial cost than the A7s.

The A7s was already on my radar when I first got the opportunity to shoot with it. Its specification is impossible to ignore for anyone interested in low light performance. The fact it’s mirrorless was, at the time, academic. Now, however, I’m sold on the benefits of its small form factor/ light weight and, well, you’ve heard that I love the EVF.

I’m fascinated to see how the dynamics of the DSLR vs. mirrorless markets plays out. I’m no analyst but it’s easy to imagine a time in the not too distant future where even the most hardened DSLR advocate is going to be weighing up the pros & cons between the two systems. Sony’s work with the A7x range surely means they’re a force to be reckoned with.

Have a question for Andrew about his long exposure and light painting work with the Sony A7s? If so, be sure to leave him a comment below!