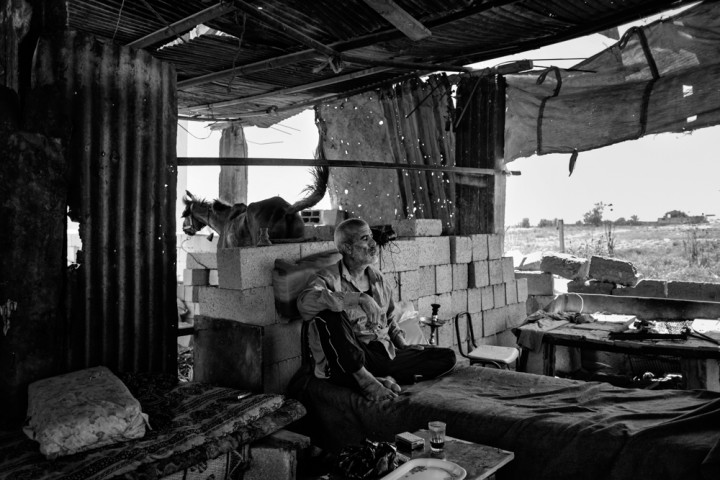

The cover image is part of the “Tramadol” story.

Welcome to our series of 100 interviews we will be holding with photographers who use mirrorless cameras for their work. “Switching to a smaller and lighter system” has become somewhat a buzz phrase as of late, but many working photographers take this philosophy seriously. From medical reasons such as resolving back and shoulder pain to the simple realisation that bigger does not mean better, photographers are turning to mirrorless systems now more than ever before.

This week’s interview is with Antonio Faccilongo, an Italian freelance photojournalist who travels the world with his Fujifilm X-T1 to document sensitive stories in difficult places. His work focuses mainly on Asia and the Middle East, where he covers social, political and cultural issues.

His work has been published in many popular Italian and International publications such as L’Espresso, Time, Le Monde, New York Times, The Guardian, and others. He has received many awards and his long term project in Palestine, “(Single) Women”, has received multiple awards including 1st Prize Px3, 1st Prize WPGA, 1st Prize Kuala Lumpur International Photo Awards and 2nd Prize IPA. His work has been exhibited in numerous international festivals including Fotoleggendo in Rome, PPA Festival in Prague, the Buenos Aires Biennial in Argentina, Foto8 Summer Show in London, PX3 in Paris and many others.

You can find out more about Antonio’s work by visiting his website.

All images in this article are property of Antonio Faccilongo and are published with permission.

1. Who is Antonio Faccilongo in three simple sentences?

A curious person, an ambitious photographer and a dreamer.

2. Among the various photographic genres in existence, you chose documentary and reportage. What prompted you to undertake this path?

During the first years, what prompted me was the desire to know the world, to spend time in contact with other cultures and to experience life as an adventure. I think it was also a way to get to know myself and my limits.

As the years went by, the desire to testify became stronger and stronger. Today it is a personal and in-depth commitment. My images are published in newspapers and are seen by many readers. They contribute to building an opinion for those who don’t already know the story or to give them a new point of view. It is a big responsibility and also a big privilege.

3. Your latest work – Tramadol – The drug of Gaza – is a reportage about the growing drugs trade in the Palestinian territory. How do you prepare a piece like this?

Good preparation before departing is essential. You need to do your research as much as possible, know the story and the politics of the territory, and read books that can help you become more familiar with the culture, the traditions and the art of that community.

The first time I went to Palestine was in 2008. Since then I developed a pretty good idea about the place and I built a series of personal and working connections that help me with my work today.

First of all, you need to verify the reliability of the news you want to document by contacting journalists and collaborators in the field, both local and foreign. After that the fundamental step is to locate the most suitable “fixer” for the story you want to tell. A good fixer will open all the doors, help you save time and money, help you meet the person you are looking for and in tense moments, he will also save your life by avoiding complicated situations.

4. Many of your shots in Tramadol give us the perception of being really close to the people and experiencing the event in first person. I tried to imagine the very short distance between you and the scene you are photographing. How much time is necessary to get that close to the person experiencing that moment?

It is a question of luck really. It’s like everyday life: there are people with whom you are comfortable right away and people whom you will never get to know. In this case, I documented the discomfort in which Gaza residents live through the abuse of Tramadol, not a story about the use of drugs or its market.

In a way the people there felt they were understood. I think they appreciated my intention to narrate their story by focusing on the need to run away from a very tense situation instead of their drug addiction.

The Palestinian people take Tramadol to overcome a sense of claustrophobia that they feel because they are confined inside a wall and they don’t have any chance to get out. A Gazawi friend that just had a baby a couple of months ago told me: my son was born with a life sentence.

I was identified by the Palestinian people as an opportunity to have a voice on the outside that could tell their stories. This made going into these situations and being accepted simpler.

5. I can imagine that you have found yourself in delicate or dangerous situations more than once. Is there a limit you impose on yourself? Is there a moment when it becomes very difficult to take a picture?

In general the limit is putting your own life, that of the person working with you or those of the people you are photographing in danger. It is not possible to set a precise rule to follow, but you need to have the sensitivity to interpret each and every situation from time to time.

There are also moments that are difficult to explain in words. You can only understand by experiencing them in person. These situations can put your own sensitivity to the test and can make you question your role in that social context. I think they are the mirror of our own conscience and of the ethics of the journalist.

6. Have you ever encountered difficult moments that stopped you from finishing the reportage?

In some situations I think it is normal to find yourself at an impasse and get the impression that you’ve already tried everything, especially when you work on sensitive topics or in troubled areas. But I believe perseverance and patience are always rewarded. Sooner or later you will meet the right person who will help you go more in depth and become more intimate with the people. That is where the story has a turning point.

One last thing and probably the most important – even if it is not acknowledged a lot by photographers – is the role of a fixer. Working with an experienced fixer who knows the needs of a journalist will open all the doors for you and will allow you to save time and money.

The fixer knows the place and the local culture, he helps you meet the person you are looking for and gets you where you need to be. In some cases, he also saves your life.

7. In some of your reportage works we can see a delicate and respectful sensitivity towards the subject being photographed. How difficult is it to document a story and at the same time satisfy the “artistic” part of the composition when you find yourself in situations with no time or when things don’t go the way you were hoping?

The photojournalist has to make decisions before, during and after the shot. They are decisions that aim to respect the readers while trying to be as honest as possible in showing the complexity of the reality. At the same time you must be respectful and grateful towards the person you photograph. One way to do this is to photograph to give a testimony and dignity to the subjects but other times the best choice can be not to photograph and share a moment instead.

A very large number of their men are in Israeli prisons. What about the struggle of the women left behind?

Click on the image to find out more about this reportage.

8. I can imagine that the final selection for every reportage is a delicate step. How many photos do you take for one story like Tramadol? How does the final selection work?

In that case I shot an average of 2000 pictures during two different trips. With other works I produced even more images. In a situation like drugs you can’t walk and take pictures freely. It is a job composed of research, long waits and sensitivity to understand when it is the right moment to lift the camera.

The editing is the most difficult part and I can’t do it alone. I am too attached to what I photograph.

When I come back from a job I still have all the emotions I felt and shared with the person I photographed on my skin. That doesn’t allow me to be lucid enough. The help from respectful photographers, journalists and photo-editor friends is essential. It is very important to be part of a team and start to ask for advice from the research step to the final edit.

9. Is there a shot in particular that you remember more than any other, maybe because of the power of the shot itself or for the situation in which you took it?

One shot I feel particularly attached to is part of my work “I AM LEGEND” about the life of Ugo Sansonetti. Ugo is a special person who has had an adventurous life full of “out of the ordinary” experiences. When he was young, he served as an admiral in the Navy, then he was a pioneer in Costa Rica. Back in Italy he became the president of the biggest frozen foods company in the world. Once retired he resumed his big passion for sports and won 52 gold medals in the diving and swimming world master series (100, 200 and 400 meters categories). The last medal he won was at the age of 93 years old. But that is not enough because in the meantime he found the time to write 4 essays about how to re-distribute wealth equally in the world and was selected by the Esa to do the first journey of an octogenarian into space to study the reaction of the human body at that age to the absence of gravity.

The photograph I chose portrays him at the swimming pool of the Italian court during a diving training session with a group of teenagers. In that picture Ugo winks – probably to focus better – but it also looks like he is winking at life itself. There surfaces his strong temperament that led him to always challenge himself without limits.

For me this picture is a hymn of praise to life and, as he said himself, to the importance of never stopping.

10. Obviously our website focuses on photographic gear so we couldn’t skip the question about the camera you are using, which is the Fujifilm X-T1. What prompted you to choose it and what lenses are you using?

After a period during which I owned double the amount of equipment to understand if the camera was effectively right for me, I now use two Fuji X-T1s with the 18mm, 23mm and 35mm for reportage, the 10-24mm for interiors and the 60mm for portraits. I am very happy with the choice I made. The quality of the images is excellent. Since I held the camera in my hands for the first time, I’ve always had the impression that it suits me perfectly. I love to be lightweight, almost invisible and don’t instill any dread in whoever is in front of me. I would never go back now.

11. What are the essential accessories you always carry with you in your bag?

The accessories that are always with me are: two X-T1s, 6 spare batteries, 4 chargers, the lenses mentioned above, a notebook for interviews and notes wrapped in a rubber band so that they wont deteriorate, a MacBook, a pen, a pencil, a cleaning pen for the lenses, a little air pump to get rid of dust on the sensor, a led light, 12 rechargeable AA batteries, two 32GB, one 16GB and one 8GB SD card, folding sunglasses, a passport, various credit cards, an external hard drive and a clean shirt.

IVF tells the story of Palestinian prisoners’ wives who have turned to sperm smuggling in order to conceive children from their husbands who are serving long-term sentences.

Click on the image to see the full reportage.

12. Photography has been changing rapidly over the past couple of years, concerning both gear as well as how images are shared. Do you find it more difficult to do reportage today? How do you see this profession evolving in the next 10 years?

I go countertrend and I believe that in the future things will get better.

I think that the digital era is just the beginning and we are still in a transition phase. All big changes need time to reach maturity and to find their own stability and awareness.

Unfortunately my generation finds itself in the middle of this change and today we are struggling to find jobs. Often the pay is not enough to cover the expenses needed to do the work in the first place so we have to think in a creative way to finance them. What prompts us to keep going is definitely not the money but the passion. Without it there would be no more photo-reporters.

Do you have any questions for Antonio about his reportage work? If so, leave him a comment below!