I have always been fascinated by astronomy and the eternal question: are we alone in the universe? NASA’s discovery of seven earth-like planets in the Trappist-1 system yesterday is exciting news to my eyes and ears. Although concrete information about the habitability of these worlds is still out of our reach, it’s a little grain of hope that I welcome as the best news of the year so far.

After scanning through various articles and videos that explain NASA’s discoveries, I started to imagine what it would be like to take photographs on one of these planets from a photographer’s point of view. Well, if you are a hopeless dreamer as I am, here are a few interesting things to fantasise about.

There aren’t any sunsets or sunrises.

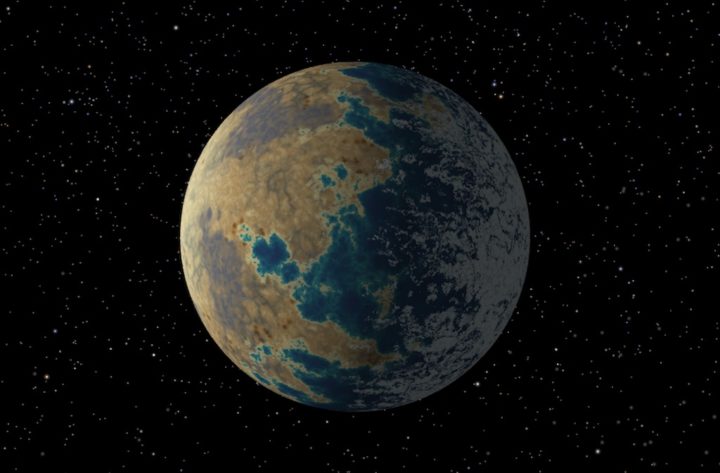

Because tidal forces from the Trappist-1 star have likely slowed down or completely stopped the rotation of their axes, the seven planets only show one face to their sun, much as one side of the moon always faces Earth. Half the planet is in constant daylight and the other half is subjected to infinite night-time. This means that there would be no daily change in the intensity of light between day and night as we witness here on Earth.

Photographers would have to travel to different areas of the planet to capture the sun in different positions. And moving from the centre of the day zone to the twilight zone would be anything but a short journey. After all, these new planets are more or less the same size as our beloved planet Earth!

And as for astrophotography, you would need to travel to the dark side of the planet to be able to capture a pitch-black sky.

Light and colour would appear very different to how they appear on Earth.

The Trappist-1 star is an ultra-cool red dwarf, which is 11% the radius of our sun. This means that the planets must orbit in close proximity in order to support liquid water and perhaps life as we know it. In fact, it takes one day for the closest planet (Trappist-1b) to orbit around its sun and twenty days for the most distant planet (Trappist-1g).

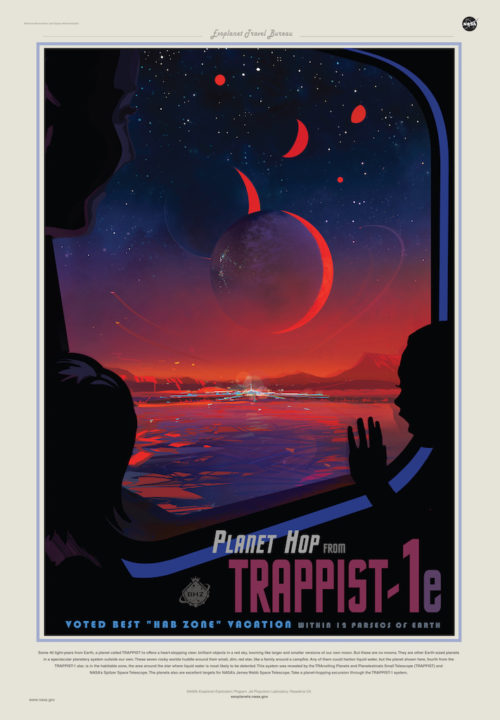

Viewed from one of these planets, the Trappist sun would appear six times larger than our sun on Earth. The light from a red dwarf is also different: it would cast a red glow across the sky and daylight would be red-orange. So despite the lack of sunrises or sunsets, you would still be able to capture those attractive warm colours we all know and love. Furthermore, vegetation would likely appear red or black, so you can picture in your head what kind of landscape you would see.

The close proximity of Trappist-1 and the various planets would offer unique landscapes and compositions.

All seven planets are close to each other, so from the surface of one of them, you would be able to see and photograph the neighbouring worlds, observe geological or atmospheric features, and even capture frequent eclipses. They could appear larger than the Moon in the Earth’s sky. Photographing events like the Super Moon is exciting on Earth, but you can imagine how much more thrilling it would be to document Super-Trappist planetary events in this new solar system.

Well, I guess the daydream ends here. The Trappist solar system is 40 light years away in the Aquarius constellation and with our current technology, it would take us 40 million years to travel there. And let’s not forget that scientists are still debating whether life around a red dwarf star is possible or not!